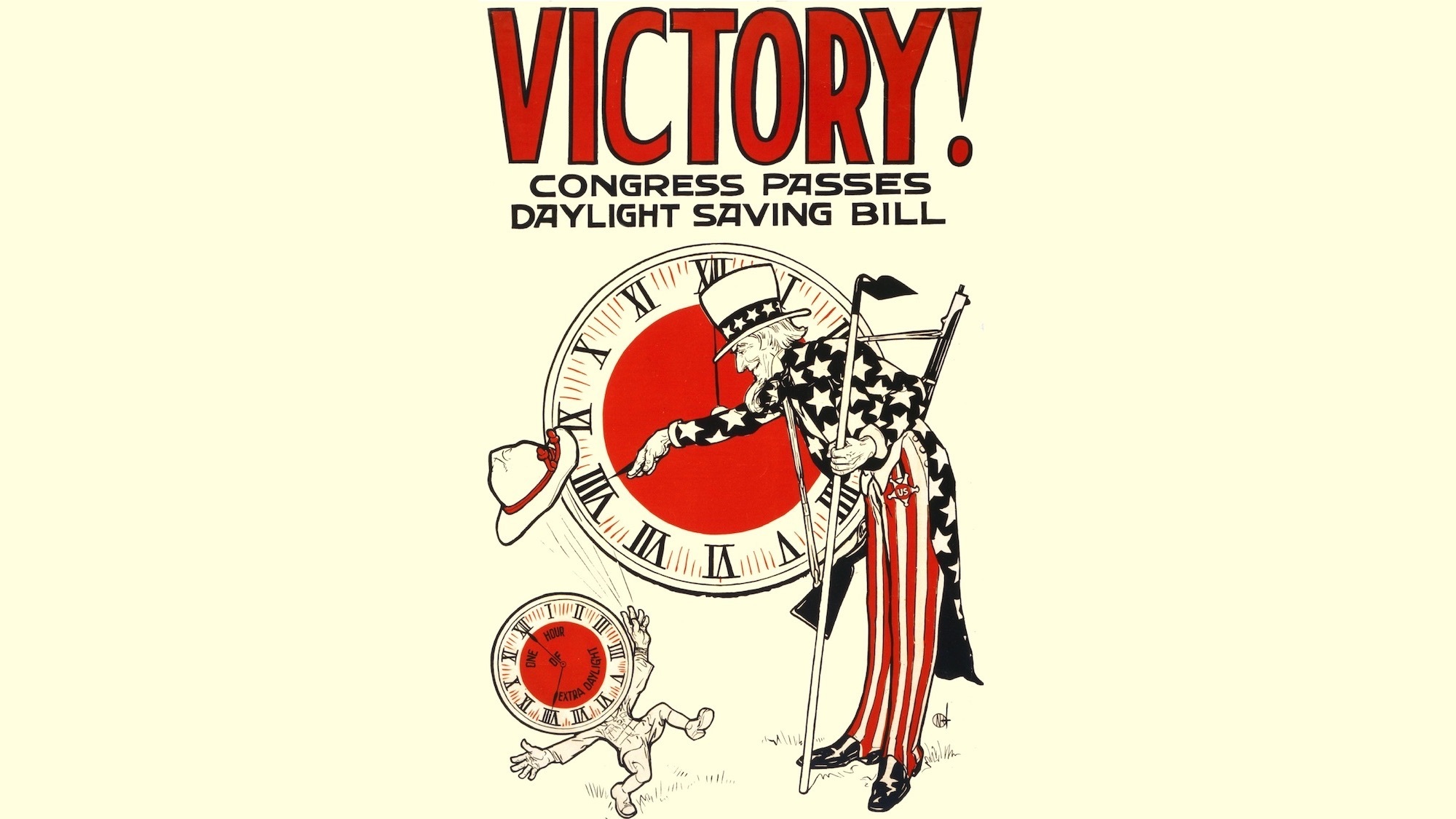

As fall approaches, so too does the end of daylight savings time (DST). On November 2nd, the hour between 1 a.m. and 2 a.m. will happen twice. When we all wake up Sunday morning, we’ll find it’s an hour earlier than it feels like it should be. Then, we’ll go about our day with a blissful extra hour of time. For DST enthusiasts, this represents a sad day that brings an earlier sunset and the start of the dreary winter months. For DST haters (like your correspondent), it represents the annual reclamation of the hour of sleep that was stolen from us six months earlier. Either way, the annual spring forward/fall back cycle remains as controversial and largely unpopular as it has ever been. The consensus amongst sleep experts and researchers is that we’d be best served just dropping the whole idea of DST and returning to plain old standard time (“ST”) throughout the year. But there’s another possibility: What if it was daylight savings time all year round? Well, that actually happened in the mid 1970s. In 1974, daylight saving time became (briefly) permanent In January 1974, clocks across the United States sprang forward, with the intention being that they would never fall back again. The policy was introduced by then President Richard Nixon as an energy-saving response to the previous year’s oil crisis, and while the initial implementation was for a two-year evaluation period, the plan was for a permanent shift to year-round later sunsets. Clearly, this did not happen, and the reasons why we still have the biannual hour switch can largely be summed up in one word: Watergate. Permanent daylight savings time lasted only a few weeks longer than Nixon himself. In late September 1974, the month after the President’s resignation, the Senate voted to defenestrate the policy. After Nixon, the prospect of permanent DST then receded into the shadows for decades, not least because federal law prevents states from messing with time and time zones. However, it has started to emerge again over the last decade—President Donald Trump is apparently a fan. The history of daylight saving time It feels appropriate, then, that the origins of modern DST can be traced back—at least in part—to another man with a fondness for golf and a desire to remake the world into one more amenable to his whims. David Prerau’s 2006 book Seize the Daylight places much of the blame/credit for modern DST at the feet of William Willett, a 19th-century British builder and avid early riser given to lamenting what he saw as the idleness of his fellow countrymen. Willett was also a keen golfer and often found himself frustrated by having to curtail a round by sunset. In 1907, Willett channeled his frustrations into “The Waste of Daylight,” a self-published pamphlet that advocated a progressive advancing of clocks during April and a corresponding winding-back during September. Willett’s primary motivation was to extend the window for post-work leisure and activity, which he argued would also improve public health—including, notably, the quality of citizens’ sleep. William Willett first proposed daylight saving time in 1907. Image: Public Domain Photo Credit: Kensington and Che Willett’s proposal was taken up by MP Robert Pearce, and barely six months later, the British Parliament found itself debating the Daylight Saving Bill, introduced in the House of Commons in February 1908. The pastoralist language used in the debate around Willett’s proposal is instructive: Proponents spoke of “wasting the light of the morning hours” and contrasted the merits of “glorious sunshine” with those of “man’s puny efforts at illumination.” A certain Lord Avebury said, “The bill not only would be a great convenience to merchants and bankers, but also, and even more important, would give more time to clerks for a game of cricket or other recreation.” The bill bounced around the House of Commons for years, never quite collecting enough votes to be passed. Willett died in 1915 without seeing his idea become reality. A year later, though, daylight savings time became a reality—in Germany. History does not remember Kaiser Wilhelm II as a fan of cricket or golf. The Frankfurter Zeitung made it clear that in wartime Germany, at least, the policy’s benefits were “in the first place of an economic kind,” with the perceived “hygienic and social” benefits being more a bonus than a motivation. A late sunset meant “mak[ing] more intense labor possible.” It also meant saving fuel. The policy was quickly adopted by Germany’s allies and neighboring countries—and, on May 17, 1916, by a sheepish Great Britain. Trying to make DST permanent today The idea of permanent DST never seems to have occurred to Wiliam Willett, but it certainly occurred to others. In the U.S., it surfaced as early as 1917 in discussions around the implementation of a seasonal DST policy similar to that pioneered by Germany. By that time, some cities had effectively already implemented year-round DST: Prerau’s book describes successful campaigns in Cleveland and Detroit during the early 1900s to alter those cities’ clocks from Central Time to Eastern Time, bringing their clocks permanently forward an hour. (When seasonal DST was implemented across the country in 1918, Detroit shifted back to Central Time; Cleveland did not.) As with seasonal DST, year-round daylight saving time was first implemented in wartime—as a result of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The U.S.’s entry into World War II was accompanied by the advent of “War Time,” which imposed year-round DST across the States. The policy was very much a wartime measure, aimed at lowering energy consumption. It was largely unpopular, and Congress wasted little time in repealing it once the war ended. But the spectre of permanent DST has never quite gone away. In 1968, Britain presented Nixon with a brief and ill-fated experiment with British Standard Time, which changed Britain’s clocks to match those of mainland Europe, which in effect meant year-round DST. The experiment did not go well, and the policy was repealed in 1970. (Seasonal DST was re-implemented two years later.) In February 1974, eighth and ninth graders board the bus at seven a.m. in the dark to head for Drake Junior High School in Denver, Colorado. Image: Denver Post / Contributor Denver Post Despite the fact that experiments with year-round DST have inevitably proven unpopular and short-lived, there are still true believers today. In the USA, curiously, the idea’s enthusiastic proponents come from one of the U.S.’s sunniest states: Florida. The most prominent modern year-round DST enthusiast has been Marco Rubio; prior to his appointment as Secretary of State, he kept himself amused with annual failed attempts to pass his “Sunshine Protection Bill,” which would allow individual states to mandate permanent DST. No, permanent daylight saving time wouldn’t be better for you But would permanent DST actually make any difference? The labels we put on time are arbitrary, and it feels like it shouldn’t matter what number we attribute to any given hour. Similarly, as anyone who has flown across multiple time zones can attest, while jetlag is objectively awful, it always goes away sooner or later as we acclimatize to whatever new time zone we get off the plane in. Shouldn’t we also be able to acclimatise to perpetually late sunrises and sunsets? Or, as one Patsy Mink—a Democratic congresswoman from Hawaii—put it in 1974, “The human being is a very adaptive animal. There is no reason we have to be a slave to the sun.” But is this true? According to a paper published in the journal PNAS this September, which models the relative effects of permanent DST and ST, the answer is “no,” humans aren’t very adaptive when it comes to the sun. The paper’s research finds that a year-round shift to DST—like the one that happened in 1974—would lead to worse health outcomes than simply staying on standard time. In particular, the paper finds that “shifting to permanent Standard Time would lead to a decrease in the prevalence of stroke and obesity.” As the paper’s co-author Lara Weed, a PhD Candidate at Stamford University’s Zeitzer Circadian Research Lab, explains to Popular Science, there has been plenty of research into the effects of the biannual shift from standard time to DST and back again, and the scientific consensus is that those effects are largely adverse. “Switching time policies can have acute negative consequences,” Weed says. “The change [in] societal time can disrupt our body clocks through changes in our light, diet, and normal timing of activities.” The results of this time change disruption manifest in effects like an increased rate of traffic accidents and workplace injuries, along with less directly visible effects like an increased rate of cardiovascular events. While changing every six months seems to exacerbate these effects, Weed and her team found that a permanent shift to DST—while less damaging than the current biannual back-and-forth—would also cause problems. Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising. Circadian rhythms are important, and there’s clear evidence that people whose sleep cycles are subject to long-term alterations are more vulnerable to the effects described in the paper. The classic example is that of people who work night shifts and sleep during the day; Weed explains, “We know there’s a link between circadian disruption, such as [that experienced] in shift work, and long-term negative cardiovascular and cardiometabolic health outcomes.” Why circadian disruption leads to these negative health outcomes is less clear. “Scientists are still figuring out exactly why this occurs,” says Weed. However, it seems that at least part of the reason is that, ultimately, standard time is a better reflection of our natural sleep cycle than DST. Related History Stories How WWII made Hershey and Mars Halloween candy kings When the U.S. almost nuked Alaska—on purpose During WWII, the U.S. government censored the weather Lip balm’s surprising history from earwax to Lip Smackers How WWI and WWII revolutionized period products The spooky (and sweet) history of fake blood Ketchup was once a diarrhea cure How scarecrows went from ancient magic to fall horror fodder Humans are diurnal, so our natural inclination is to be most active during daylight hours. As such, it makes sense that we’re given to rising with the sun and going to sleep once it sets. Weed explains that waking up before the sun disrupts this rhythm: “We need light in the morning to regulate the circadian clock,” she says. “Compared to Standard Time, permanent DST has darker mornings, which can make it more difficult to stay in sync.” In other words, we are slaves to the sun. The paper is careful to note that its models and findings are applicable specifically to the contiguous continental United States. This is both because of latitude-specific factors like quantity of daylight hours, length of twilight, etc., says Weed, and also because even regions that are similar to the U.S. in these respects may differ socioeconomically and/or culturally. That said, Weed does note that the circadian modelling she and her team carried out for the paper may have utility beyond the United States. The findings would just need to be used in conjunction with locally applicable health data. The effects of permanent daylight saving time Back in the U.S., however, it seems like Nixon’s 1974 experiment could provide valuable real-world data for researchers. Unfortunately, Weed says she is not aware of any specific research data on the period. In broad terms, stroke rates have declined steadily across the U.S. since World War II. As per the CDC, there was no apparent disruption to this trend in the years succeeding the permanent DST period—although, of course, the sheer quantity of variables involved make it almost impossible to identify any sort of correlation—let alone causation—from such high-level numbers. Obesity rates, meanwhile, have risen dramatically since 1974, a situation that has led to moral panics around the “obesity crisis,” endless hand-wringing from scientists, politicians and nutritionists. Again, this is an intimidatingly complex and multifaceted public health issue, and it feels pretty much impossible to figure out how, if at all, it was affected by a brief experiment with permanent DST in the mid-1970s. But if the scientific verdict on the U.S.’s brief flirtation with permanent DST remains ambiguous, the public’s verdict was significantly less so. As discussed above, Nixon’s resignation effectively ended the perma-daylight experiment, but even without the intervention of Woodward and Bernstein, it seems unlikely that the policy would not have lasted. A New York Times report from the time reveals that while the idea of a longer post-work period of daylight was initially popular, the reality of getting up before the sun every morning proved less attractive once winter arrived: Public support for the policy plummeted from 79% in December 1973 to just 41% in February 1974. If anything, the lesson of 1974 is probably that we really should just listen to the experts who’ve been telling us for decades to stop messing around with time. The post The U.S. tried permanent daylight saving time—and hated it appeared first on Popular Science.

Tags:

#Science

#Energy

#Environment

#Military

#Sustainability

#Technology

Original Source

This article was originally published by Popular Science.

Quick Actions

Article Info

- Published

- Tuesday, October 28, 2025

- Source

- Popular Science

- Author

- Tom Hawking

- Reading Time

- 11 minutes

- Category

- Science